This post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog on 23 January 2015.

English is a truly global language with hundreds of regional variations worldwide, including over 50 dialects of British English alone. It is also the primary language of the internet, and the virtual world has spawned its own varieties of English too. These online dialects, often spread by memes, have been around long enough now for a pattern to be identified – a path well enough worn for you to identify emerging linguistic memes – or even create your own.

Long before social media – which itself has only recently caught on to the power of image-sharing – pictures were widely distributed via the internet and helped spread memes. Today, social media accelerates this process. From Grumpy Cat to First World Problems to One Does Not Simply Walk into Mordor, images with captions make great online memes, as they are so shareable. These examples all use standard English.

Long before social media – which itself has only recently caught on to the power of image-sharing – pictures were widely distributed via the internet and helped spread memes. Today, social media accelerates this process. From Grumpy Cat to First World Problems to One Does Not Simply Walk into Mordor, images with captions make great online memes, as they are so shareable. These examples all use standard English.

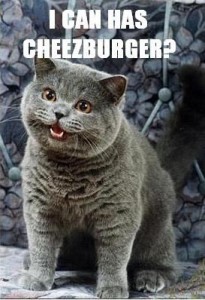

Yet captioned images can also be used to propagate non-standard dialects – such as LOLcat, Doge, and Ermahgerd. These develop into new, playfully deviant varieties of English, with their own rules of syntax, spelling, and grammar. Linguistic memes share certain characteristics: they pair an engaging image with a compelling caption to create a funny or relatable situation; they use a specific font; and they follow consistent linguistic rules.

Raining LOLcats and Doges

The oldest of these is LOLcat, or LOLspeak – LOL being the textspeak acronym meaning ‘laugh out loud’, and cats being the most popular images shared online. Starting in 2005, but with precursors dating as far back as the 1870s photography of Harry Pointer, LOLcats are images of cats overlaid with words in uppercase Impact or Arial Black. These act as speech bubbles for the hilarious things cats say, such as “I Can Has Cheezeburger?” – the original phrase, which led to a website of the same name. Recently, OxfordWords gave you the opportunity to generate your own LOLcat speak.

More recently dogs have got in on the act – specifically one breed, the Shiba Inu, who, since 2013, has used short phrases in multicoloured lowercase Comic Sans to express an internal monologue of wonderment in broken English. Doge relies more on idiosyncratic grammar than (mis)spellings and textspeak – though these are sometimes employed too. For example, a Doge meme relating to Wikipedia was captioned: “wow / many edits / so Internet meme / much wiki / very readers / how to article? / such neutral.”

More recently dogs have got in on the act – specifically one breed, the Shiba Inu, who, since 2013, has used short phrases in multicoloured lowercase Comic Sans to express an internal monologue of wonderment in broken English. Doge relies more on idiosyncratic grammar than (mis)spellings and textspeak – though these are sometimes employed too. For example, a Doge meme relating to Wikipedia was captioned: “wow / many edits / so Internet meme / much wiki / very readers / how to article? / such neutral.”

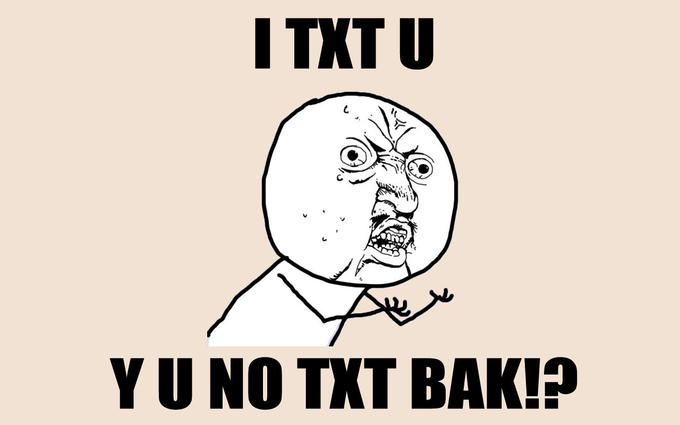

Ermahgerd! Y U No Txt Bak!?

Humans feature in language memes too. “Y U No” Guy pairs uppercase textspeak with a stick figure sporting a furious facial expression taken from a character in Japanese manga series Gantz. The original phrase was: “I TXT U / Y U NO TXT BAK!?”

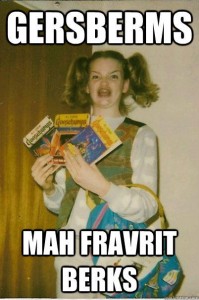

Ermahgerd (translation: “Oh my God”) emerged in 2012 as a picture of a girl excitedly holding three books in the children’s horror fiction series Goosebumps with the caption: “GERSBERMS / MAH FRAVRIT BERKS” (“Goosebumps, my favourite books”). The captions are meant to sound like a speech impediment caused by the use of an orthodontic retainer.

Idiosyncratic English

Memetic dialects tend to use idiosyncratic forms of English for comic effect. LOLcat and Doge both use a sort of anthropomorphized baby-speak. Is this the sort of broken English cats and dogs would use, if they could speak? It’s  more to do with the language we use to talk to our pets – ‘pet-directed speech’, as it’s known (no, really – there are studies). This is akin to ‘infant-directed speech’ (which was called motherese when I was a psychology undergraduate, before people realized that fathers spoke to their children too). Memes featuring human characters require a different approach – Y U No uses textspeak, and Ermahgerd uses phonetics based on a speech impediment – but the possibilities are endless.

more to do with the language we use to talk to our pets – ‘pet-directed speech’, as it’s known (no, really – there are studies). This is akin to ‘infant-directed speech’ (which was called motherese when I was a psychology undergraduate, before people realized that fathers spoke to their children too). Memes featuring human characters require a different approach – Y U No uses textspeak, and Ermahgerd uses phonetics based on a speech impediment – but the possibilities are endless.

Whatever deviations from standard English you use, the key is to be distinctive and consistent. This will help your meme pass from image to text. You know a meme has really caught on when you no longer need to pair it with an image. Doge has a grammatical structure identifiable enough to be used as text only, such as on Twitter. See @WowSuchDoge, @ItsDoge, and @DogeTheDog for examples. You can even find a full linguistic deconstruction online, along with a synopsis of Romeo and Juliet written in Doge.

How to create your own linguistic meme

Do you have a non-standard form of English you use to speak to certain friends? Perhaps in texts and emails? Such ‘private languages’, full of neologisms, catchphrases, and idiosyncratic spellings and grammar are a good place to start (and you don’t have to go as far as Stanley Unwin).

- Decide on your linguistic rules and be consistent.

- Pick a font and colour scheme and stick to it.

- Pair your text with an image. Animal or human, use your captions as speech bubbles or internal monologue. Create your images with graphics software, or use a site like Meme Generator (which you can also use to find and customise popular memes).

- Use social media to share your meme – Twitter, Facebook, Instagram. The essential characteristic of memes is that they spread. Social media can make this happen rapidly.

- Track your meme. You’ll know it has caught on when other people start using it – and particularly if it passes into text only without needing to be paired with an image.

- Submit your meme to Know Your Meme. It will be an ‘official’ meme once confirmed there.

Wow. Amaze create. Very meme. So language.